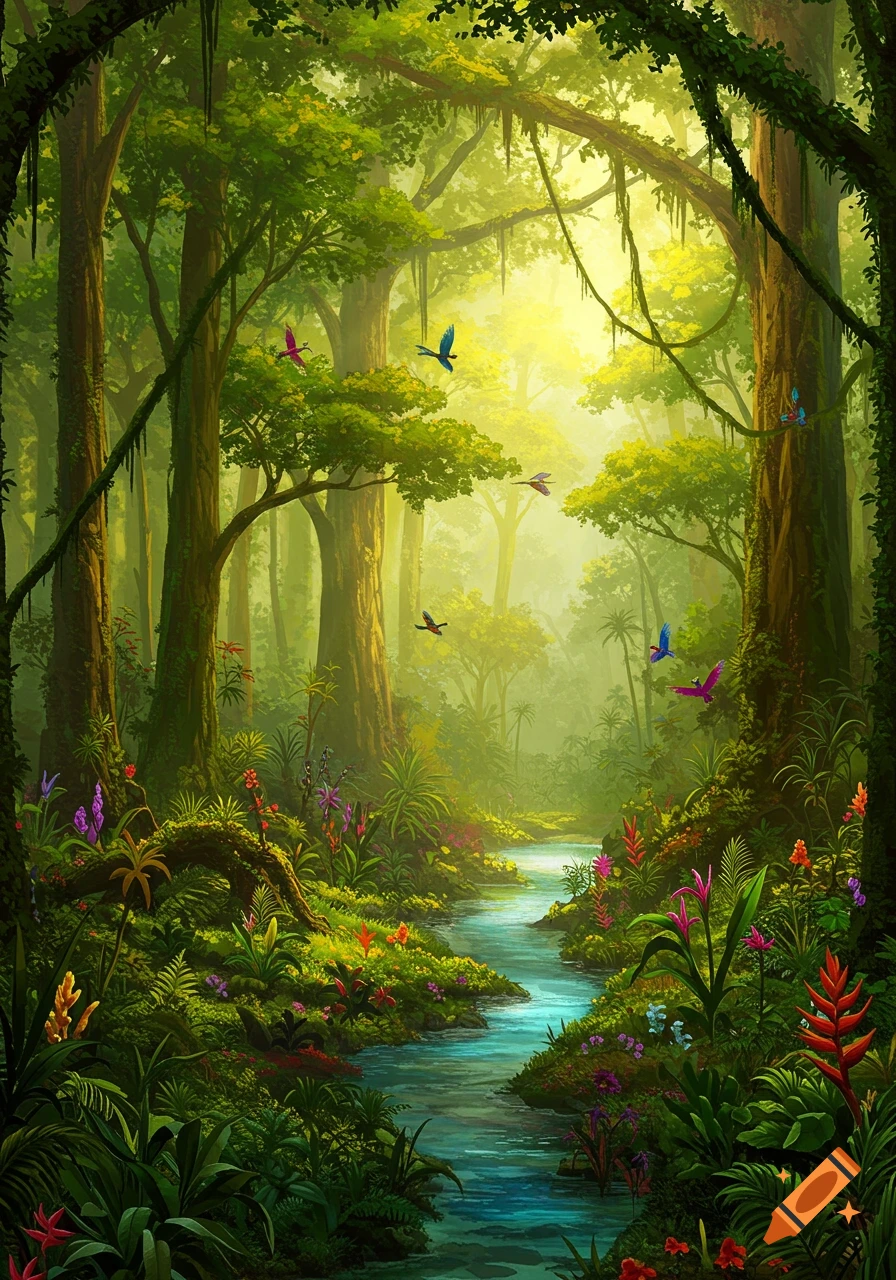

Detailed fantasy art of a lush prehistoric jungle with a river, mountains, diverse creatures, and a human at sunset.

It is highly improbable that an unarmed human would be safe visiting a terraformed planet 100 million years after the introduction of Spilogale pygmaea (pygmy spotted skunk), Bassariscus astutus (ringtail), Hemigalus derbyanus (banded palm civet), and Echinosorex gymnura (moonrat) as the sole vertebrate species, even with the specified environmental conditions and limitations on protostome evolution. The immense timescale of 100 million years allows for significant evolutionary changes, making predictions of safety extremely difficult and largely speculative. Evolutionary Considerations Over 100 Million Years The primary factor undermining the safety of an unarmed human in this scenario is the vast evolutionary timescale. One hundred million years is an immense period, far exceeding the time it took for dinosaurs to rise, dominate, and fall, or for mammals to diversify into their current forms. For context, the last common ancestor of humans and mice lived approximately 80 million years ago [1]. Even with a limited starting set of four vertebrate species, the potential for evolutionary divergence and adaptation is enormous. Adaptive Radiation: Given a new, resource-rich environment with no existing vertebrate predators or competitors, these four species would likely undergo significant adaptive radiation. This process involves the rapid diversification of a single ancestral lineage into many new species, each adapted to exploit different ecological niches [2]. For example, See more